Appendix: Geography & Culture§

This England is not, quite, the England you may know.

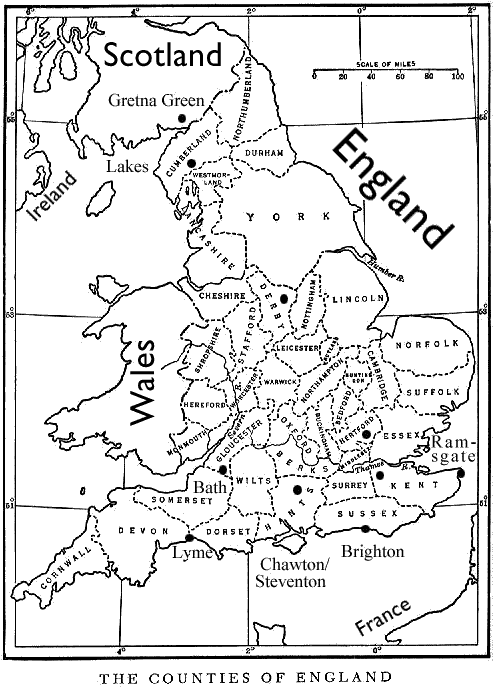

Geography§

Image courtesy of The Republic of Pemberley.

England at this time is just starting to be made small: transportation on the stage coach is getting both faster, and more affordable for more people. But there’s still a lot of regional variation.

For our purposes, we’ll divide England into a few macro-regions, and talk about each. Then, there are three cities that deserve special attention as noteworthy cities of the age: London, Bath, and Brighton.

South East§

Consisting of the counties of Bedfordshire, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Essex, Hampshire, Hertfordshire, Kent, Oxfordshire, Surrey, and Sussex, this is very much what you think of when you think of Jane Austen’s England. Rich farmland supports many small towns. You’re not too far from London, and so the rich who spend the Season in London and the off-Season at their country houses are most likely to be found in this region. The seat of the foremost of Anglican bishops is here, too, at Canterbury.

This is also where some of the most popular beaches in England are to be found, and as sea-bathing has become a fashionable medical (or quasi-medical) cure, towns like Brighton have begun to boom. But this coast is also where a French invasion would be most likely, and so the Navy patrols extensively, and militiamen walk the coast keeping an eye out for enemy sails. Meanwhile, the men of the Cinque Ports believe their ancient rights let them import luxury goods like brandy and silk from France without tax, while the Revenue men brand them smugglers.

Local legends speak of the sons of the giant Goemagot, who stalk the hills at night seeking vengeance for their father, who was slain by one of the first of English kings.

South West§

Consisting of the counties of Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Somerset, Dorset, Devon, and Cornwall, the South West covers a range of landscapes and lifestyles. In Cornwall, life is hard and local politics is very corrupt. Mine-owners seek to extract what tin and copper remain, while fishermen turn to smuggling and piracy to make ends meet. But in the north and east of this region, the land is more giving and there are even fashionable resorts, like Bath and Lyme Regis, and the wealthy trading port of Bristol. While any slave who once walks on English soil is free, that same privilege does not extend to British holdings in the West Indies, and many abolitionists decry Bristol as a city made rich through great injustice.

Perhaps the most striking natural feature of this region is Dartmoor, a large area of moorland in the middle of Devon. It is covered with sparse vegetation and hills topped with granite pillars known as tors. At night the mists lie heavily on the moor, and locals say you can hear the fairy-hounds baying and the Wild Hunt riding through the air.

East England§

Consisting of the counties of Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire, Norfolk, and Suffolk, the East is marked by low-lying fens and extensive navigable waterways called the Broads, and few here are not comfortable on a boat. Much of the land is even reclaimed wetlands. But it is fertile land, and the farmers of the East have long been proud of their wealth and position. That is changing, as the mills of the North and the Midlands begin to eclipse the wealth one can find in sheep and horses.

No one likes to see their stability and status vanish, and those who live in East Anglia are no different. They are trying to diversify, and trying to use the force of government and law to shore up their position. The East was a stronghold of the Puritan Parliamentarians during the civil war, though, and their factions ultimate loss has not left them with much credit among the subsequent monarchs. So the landholders will go to great lengths to emphasize their loyalty to the crown.

The fens hold many ancient secrets, from the bodies of the first Danes to land on English soil, to the great one-eyed ghostly dog the locals call “Black Shuck”. He protects the souls of the dead, but ushers more into their number whenever he appears.

Midlands§

Consisting of the counties of Derbyshire, Herefordshire, Leicestershire, Lincolnshire, Northamptonshire, Nottinghamshire, Rutland, Shropshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire, and Worcestershire, the Midlands are divided east-to-west by the line of the old Danelaw. The region is home to a mixture of the rich farmlands of the south, the growing industrial power of the north, and a foment of natural, spiritual, and mystical philosophy all its own. Great minds like that of Sir Isaac Newton, Erasmus Darwin, and James Watt all call or called this area home, and while the philosophical Lunar Society of Birmingham has collapsed, its influence is still felt.

It is said that the most powerful and malicious fairy of the Midlands, Black Annis, was trapped in her cave in the Dane Hills when a powerful magician of the previous age barred the entrance with a great oak tree.

The North§

Consisting of the counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, Durham, Lancashire, Northumberland, Westmorland, and York. The North has for a long time had a distinct identity from the rest of England. In the aftermath of the Norman invasion, and William the Conqueror taking the throne, many of the Northern lords refused to bend the knee to him, and rallied behind the last Anglo-Danish claimant to the throne. When they lost, their lands were ravaged, their people killed, their treasures taken. This wrong has not been forgotten, and a kind of distrust and enmity remain between Northerners and Southerners, though many no longer quite know why.

Compounding matters, the land of the North is now yielding a new kind of wealth, a wealth derived from mines and factories. Textiles, coal, and iron are making a new set of people in the North rich, and driving yet others into more abject poverty. The followers of old King Ludd, the ancient fairy king of the North, have been breaking the industrial looms to protest this oppression, and the government has held show-trials in this past year, and made “machine breaking” a crime punishable by death. The government is hoping that by the brutal and indiscriminate application of violence, they may suppress the movement and leave mill owners secure in their position.

London§

Famously, the poet Shelley once said “Hell is a city much like London… small justice shown, and still less pity.”

London is the driving force of encroaching modernity. If anything will close the gates to magic and Fairyland again, it will come from London. Magicians find it more difficult and dangerous to cast spells in London, just as they do when they are further from England’s shores.

While the action of a game may move to London, I strongly encourage you to not set a game here.

Bath§

Perhaps no city more fully captures the spirit of the age than Bath. Once a Roman city named Aquae Sulis, the city has endured and changed for centuries, always drawing people with its healing waters. Now, Bath has become the most fashionable destination for the gentry who wish to escape the stench and hazards of London.

If you wish to see and be seen, you could do worse than attending a dance at the Assembly Rooms, drinking the waters at the Grand Pump Room, or taking a walk along the Royal Crescent in front of the Palladian townhouses. Anyone who is anyone will be there.

Brighton§

The town of Brighton was in a steep decline until two events caused it to surge upward again: the increasing popularity of sea-air and sea-bathing, and the presence of the Prince Regent himself in the town. Many other luminaries have gathered here as a result, including the great Indian surgeon Sake Dean Mahomed, who has just moved back to Brighton to open his Indian Medicated Vapour Bath, where he uses his technique of shampooing as a medical treatment.

The Prince Regent, meanwhile, has made his home-away-from-home here in the form of the Royal Pavilion, where he holds great parties for his inner circle, and meets not-so-discreetly with his secret wife, Mrs. Fitzherbert. The Pavilion is built in a neoclassical style, but the Prince Regent has been considering rebuilding it in an Indian style to match the stables.

Religion§

Religion in the Regency deserves some particular mention. As many dissertations can and have been written on this subject, and on each religion mentioned here, this is necessarily an overview only.

Anglicanism§

The state religion of the United Kingdom at the time is Anglicanism. This is a branch of Christianity usually identified as Protestant, though some theologians in the period and before have insisted that it represented a middle way between Protestantism and Catholicism. The head of the Anglican church is actually the English monarch, but the de facto head and primus inter pares is the Archbishop of Canterbury. Anglican ministers not only can marry, but are expected to do so to set a good example for their parishioners.

As the emergence of the Anglican church more or less coincided with the disappearance of English magic, the church has never had to come to an official policy on the matter in any real way. Mostly, Church doctrine borrows from the earlier stance of the Catholic church in England: it is unseemly for a man of the cloth to practice magic, but it is not as though magic is itself sinful or wicked.

Catholicism§

Catholicism is often seen in the period as a religion of the Continent, but it has, of course, deep roots in the British isles. It is at this point still the majority religion in Ireland, and widespread in England despite years of official repression. As of 1791, Catholic worship has been made legal again, but Catholics are still barred from certain public positions, such as sitting in parliament. Catholic marriages were not legally recognized, either.

While the Mother Church in Rome looks down on magic, it has usually looked down at least as much on the idea of witch-hunters. English Catholics in particular though tend to accept the ancient laws by which magic might be practiced, as long as it didn’t interfere with the activities of the Church.

Methodism and its cousins§

In the early 18th century, Anglican priests John Wesley and his brother Charles developed a theology and practice of Christianity that they insisted was entirely in line with the Church of England, but which the Church saw as a threat to its power structure. Because of their reputation at school for following a strict code of holy behavior, they, and eventually their followers, were labeled “methodists”.

While superficially similar to Calvinism, in that they preached salvation through faith alone, they believed in free will and the ability to choose faith. They were known for preaching in the open air and to the poor and those that the Church of England neglected, and without regard to parish boundaries. This last point, and their encouragement of lay preachers, made the official power structure of the Church resent and suspect them. At this point, Methodism is present all over the country, but has begun to really take off in Wales.

Methodists have had precious little time to come to any conclusions about English magic, but so far the general consensus is that it is a practice that makes it all too easy to sin, and therefore should be avoided by all who wish to enter Heaven.

The Society of Friends (Quakers)§

In the middle of the 17th century, a man from Leicestershire named George Fox came to understand that it was possible for anyone to have a direct experience of Christ, without the intercession of clergy. He started a movement, and his followers formed a small but weighty set of people throughout England. While they had especial success in the now-independent American colonies, a surprising number of notable merchants and craftspeople in England counted themselves as members of the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers as others called them.

The Quakers rejected the hierarchy and structure of the Church of England, and preached and practiced a life of material simplicity, honesty, and peace. Many of them rejected slave-produced goods, like cotton and sugar, and many of them advocated for abolition of the practice of slavery in England’s colonies, such as the West Indies.

While they were never very many in number, their impact on England of this time was outsized.

The Quakers are riven in two on the question of English magic. Some see it as a natural and therefore Godly English practice which is being revived. Others see it in light of the biblical Witch of Endor, as a practice which God forbade to humans. However, no Quaker would lift a hand to a magician either way, letting any judgment be God’s to give.

Others§

There are many other religions and denominations to be found in England at this time: Presbyterians (mostly from Scotland), a decent Jewish population (mostly of Sephardic descent, from Spain and the Lowlands, and mostly living in or near London), and some Muslims (mostly lascars originally from Bengal and Gujarat, now living in port towns). Look up Daniel Mendoza, the inventor of Scientific Boxing, or Sake Dean Mahomed, who introduced shampoo to England.

Terms of Address§

A major point of etiquette in this time and place concerns how two people might address each other. Titles, family names, and personal names all play a part, as do relative social standing and intimacy.

First, if you are addressing someone with an actual title (such as the duke, marquess, earl, viscount, or baron of, say, Newland), “my lady” or “my lord”, or “Lady Newland” or “Lord Newland” will suffice. A baronet or knight may be “Sir John”, and a baronetess or dame would be “Dame Mary”.

Most people, however, neither have titles themselves, nor regularly interact with those who do. For addressing a superior, or an equal with whom you are not especially intimate, “Mr.” or “Miss” or “Mrs”, and then their surname, would be appropriate. This includes clergy; while you might address a letter to “the Reverend Smith”, you would address him in conversation as “Mr. Smith”.

When talking about siblings, it is normal to use the first name to make clear who you mean, such as “Miss Elizabeth Smith”, or perhaps even just “Miss Elizabeth” if you are intimate and the context is casual, but the eldest unmarried daughter would usually simply be “Miss Smith”.

When you are close with a man, and the context is intimate, it is normal to use simply his surname: “Smith”. For a woman, one might use simply her personal name, “Mary”, but this demands a much greater degree of intimacy, especially if used by a man.

Social inferiors may be referred to simply by their personal name, and if they are a servant with an unusual or noteworthy personal name, it is not unusual to instead call them by one more mundane, so an “Ichabod” may end up being called “Jacob”, or similar.

Currency§

The currency of England at this time can be notoriously confusing, but a little guide should help. What’s crucial is to remember that this is a pre-decimalized currency, but that there is an essential unit and subdivisions, just like you’re used to.

The basic unit is the pound, which is divided into twenty shillings, each of which are in turn divided into twelve pence. An amount of two pounds, four shillings, and sixpence might be written £2 4s 6d, or £2/ 4/6, and said as “two pounds, four shillings and sixpence”, or “two pounds, four and six”.

The penny, the smallest unit, was sometimes further divided into halves and quarters, the ha’penny or the farthing. That even a quarter of a penny had some purchasing power should indicate first the inflation that has happened since (one pound in the period is roughly the equivalent of fifty pounds today) and the extreme wealth disparity present in England at the time. The working poor would expect never to handle a bank note, as seeing that much money together at one time would be rare, while the wealthiest landlords would expect tens of thousands of pounds a year simply from rents and investments. This situation was exacerbated by landholders engaging in the practice of enclosure, that is, removing access to what was formerly common land, and reserving it for their own private use.

Where many stumble with English currency is that many peculiar coins had nicknames, from the groat (a four-pence coin), to the crown (five shillings), to the guinea (a pound and a shilling, traditionally used to include a tip for any artisan whose services were expensive enough to merit a price in pounds).

The Magic of England§

There has always been another England. It lurks on the edge of perception, it appears when you don’t look right at it. Alfred Watkins sensed something of it when he wrote The Old Straight Track. William Blake referred to it when he wrote of “our clouded hills”. This is an older, stranger, other England. It may as well be called Annwn, Avalon, or orbis alius.

But as the Enlightenment opens many doors, so too does it close some. No one has accidentally or purposely walked into that other world for a long time now. The old fairy roads that led out of England have been long closed. Until—that is, until now.

Perhaps it is the king’s madness that has changed things, or perhaps it is the renewal of worship of old king Ludd in the North. Perhaps it is simply that the stars are right. But the Old Roads are opening, mirrors and rivers and clouds and rain once again bring visitors. Magic is returning to England.

The Realms of Fairy§

There are a number of fairy realms that the magicians of old wrote about, some of which are still remembered, and some of which may be accessible to the new magicians of the age. As no mortal has been to Fairy in three hundred years, and time moves very differently in Fairy, these places may be very different by now.

The Iron Coast§

The skeletons of ships broken along the hidden shoals, endless mists and howling winds, riches untold hoarded by the merfolk below the surface, with beautiful features and the teeth of eels. Most non-aquatic people here travel by rowboat, as it is safer than being at the mercy of the winds, and safer than traveling the narrow winding track along the clifftops.

Naddercott, the serpents’ wood§

What is tree and what is snake is hard to tell, and round the roots the adders dwell. Light and shadow play around, as serpents slither o’er the ground. But Adder’s wise, as well as fell, and if you pay, he’ll secrets tell.

The Manor§

Each room opens up on to the next, an endless series of chambers and galleries in enfilade. The windows look out onto enclosed courtyards, offering no escape from this endless architecture. The courtyards contain sculpted topiaries, in the French style, and fountains, and statues that look just a little too lifelike for a magician to be certain that they weren’t once living people.

The Greenspace§

Somewhere in Fairy, if you stray and don’t think about where you’re going, you may find a glade in the forest. It’s always summer, and the weather is always perfect. There’s a white stag you can see if you’re lucky, just flitting off into the trees. This is where fairies sign their treaties and meet with no weapons in their hands. This place is sacred, and a mortal trespassing in it will earn a death sentence. But as long as they remain in the Greenspace, no fairy may lift a finger against them.